The Lilbourn Mace

One of the most iconic artifacts in the Museum of Anthropology collections is the chipped-stone mace (MAC1971-0578) from the Lilbourn site in New Madrid, Missouri. The form is unique to the late-prehistoric Mississippian period, and probably dates to the late 13th or early 14th century.

Lilbourn (23NM38) was a fortified mound site with radiocarbon dates indicating an occupation from ca. mid thirteenth to early fifteenth century. The mace was found during excavations undertaken by Mizzou’s Carl Chapman because construction of a public school building and sewage lagoon were to destroy the site.

Besides appearing as artifacts, such maces are shown on pottery, shell, copper, and as petroglyphs—including examples at Washington State Park. One of the most famous examples of Mississippian representational art—the copper repousse Rogan plates from Mound C at Etowah, Georgia—depict a winged figure brandishing a decorated mace in one hand, and a human head on the other. The Rogan mace seems to be decorated—probably with paint and feather streamers—and traces of similar decoration have been found on actual chipped stone maces at Spiro Mounds, Oklahoma.

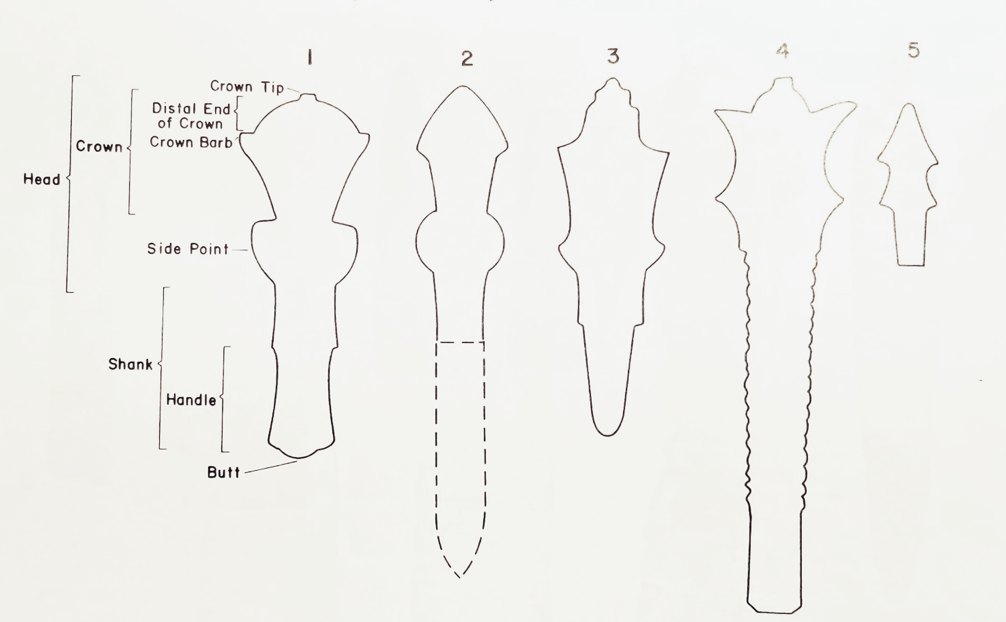

Five different forms of crowned mace have been identified by Jim Brown (1996); the Lilbourn mace is one of the finest examples of his Type 1. This particular form is probably the most common type and has been found as far north as central Illinois and as far south as a site in Ascension Parish, Louisiana. One example was even found near the Susquehanna River in New York. In some areas—notably parts of Tennessee—this form is absent, and seems to be replaced instead by the similar Type 2 form, which lacks the broad curved-and-barbed tip.

Brown has argued that maces, long thin-edged bifaces, and axes often substitute for one another, serving the same “sociotechnic” function—which is to say a purpose that’s as much or more social and symbolic as functional in the narrower sense. Certainly maces, long bifaces and axes are found together in a few instances, as at Spiro and in the famous Duck River cache from just south of the Link Farm site (40HS6) in Humphreys County, Tennessee.

For my part I’m unconvinced, largely because prehistoric artists went to such trouble to distinguish the different forms, both as actual objects and in representations. In one example--the Douglass gorget from New Madrid County, Missouri (part of the National Museum of the American Indian collection in Washington) the figure wields a hafted axe, while a Type 1 crowned mace is tucked neatly into the figure’s sash. My own guess is that as symbolic weapons such stone objects had certain parallels, yet the distinctions between them were laden with meaning and significance.

But there’s good reason to think that the chipped stone archetypes, however remarkable, are the exception, rather than the rule. In some cases the maces are shown broken, and in those cases the mace is bent and partially fractured in a way impossible for chipped stone, but plausible for wood. Broken maces are depicted on two engraved marine-shell cups from Spiro Mounds (cups 55 and 56), on engraved pottery (e.g., the so-called Robert jar, a Walls Engraved jar from the Young site, Crittenden County, Arkansas), and repoussé copper plates (e.g., the Upper Bluff Lake plate from Union County Illinois, first depicted by Cyrus Thomas in 1894; in all these cases the mace is partially split and broken.

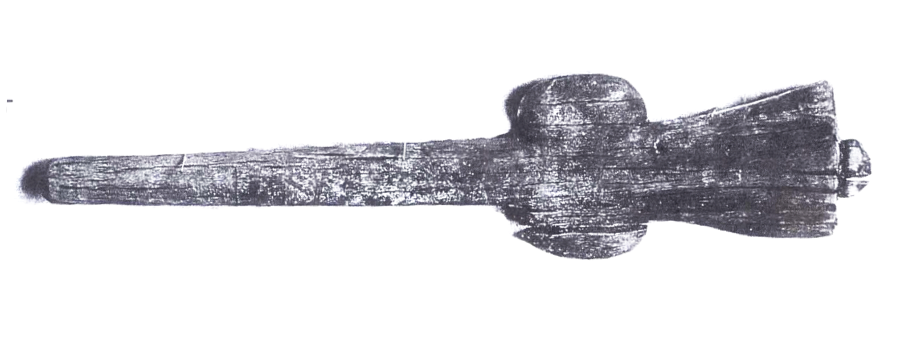

And, as it happens, in the rare cases where wood is preserved from late prehistoric contexts we sometimes see just such clubs made of wood, not stone. A typologically-correct Type-1 crowned mace was recovered from deposits at Key Marco, Florida, and is now in the Smithsonian’s collections (BAE No. 40659).

We can see a similar pattern in wooden-hafted axes; in cases where preservation is excellent we find the wooden hafts intact, bit still in place, but there are also masterpieces of prehistoric stonework that recreate the entire axes, including bit and full haft, from stone.

The Lilbourn mace, MAC1971-0578, cast replica

Note: Because the Lilbourn mace was found in association with human remains we are not showing either the burial or the original object, but rather a replica.

The Rogan Plate, recovered in the late 19th century from Mound C at Etowah, Georgia. Mound C was the tallest of Etowah’s mounds, some seven stories tall. The plate is believed to date from the Early Wilbanks phase, AD 1250-1325.

Crowned mace types, after Brown (1996). Type 1 is the most widely distributed form in both physical and iconographic terms.

The Duck River cache, a group of 46 stone objects found by a workman in 1894 near the Link Farm site at the confluence of the Duck and Buffalo rivers in Humphreys County, Tennessee, now at the University of Tennessee McClung Museum.

Line drawing of the Douglass gorget (MO-NM-X3), from an unknown site in New Madrid County, Missouri, Now in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History

Engraved marine shell cup 55 from Spiro Mounds, Leflore County Oklahoma, showing broken maces. These depictions of broken maces are common enough to be a defined motif for engraved shell art. Cup is in the Braden B style. Three matching fragments, two from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (USNM448871 and 448820, both acquired from the Meyer Collection), and Sam Noble Museum, University of Oklahoma (UOSM LfCrI B62-74).

Wooden mace from Key Marco (8CR48), Florida. Excavations by Frank Hamilton Cushing and the Pepper-Hearst expedition into the so-called Court of the Pile Dwellers at Key Marco recovered a range of perishables, preserved in the waterlogged soil.

Mississippian monolithic axe, Gilcrease Museum 61.18910

References:

Additional Readings

Brain, Jeffrey P., and Philip Phillips

1996 Shell Gorgets: Styles of the Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric Southeast. Cambridge: Peabody Museum Press.

Brown, James A.

1996 The Spiro Ceremonial Center: The Archaeology of Arkansas Valley Caddoan Culture in Eastern Oklahoma. Ann Arbor: Memoirs of the Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan No. 29.

Chapman, Carl H., and David R. Evans

1977 Investigations at the Lilbourn Site, 1970-1971. The Missouri Archaeologist 38:70-104.

Cushing, Frank H.

1897 Exploration of Ancient Key Dwellers’ Remains on the Gulf Coast of Florida. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 35(153):329-432.

Evans, David R.

1977 Special Burials from the Lilbourn Site. The Missouri Archaeologist 38:111-122.

Phillips, Philip, and James A. Brown

1978 Pre-Columbian Shell Engravings From the Craig Mound at Spiro, Oklahoma. Cambridge: Peabody Museum Press.

Thomas, Cyrus

1894 Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, DC: Twelfth Annual Report, Bureau of American Ethnology

Thruston, Gates P.,

1897 The Antiquities of Tennessee and the Adjacent States, 2nd ed. Cincinnati: Robert Clarke Co.